|

Professor Ramona M. Silver Philosophy and Humanities Three representative 20th century Californian photographers, and their use of technology as a means towards artistic contemplation. Louis Daguerre of France is credited with the invention of photography in 1839. Within a year of its announcement, photography was being practiced by artists and craftsmen all over the western world. A mere decade later, with the discovery of California gold in 1849, photographers were swept up in the westward exodus, where they were astonished by the natural beauty and grandeur of this previously unexplored region. Reflecting the awe and scope of such period painters as Bierstadt and others, the great early western photographers used primitive mammoth size cameras and painfully slow processes to capture the unimaginable experience of the rugged Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valleys, the vast Giant Redwood and Sequoia groves, the Central Valley, and the Pacific Coast. These early western photographers included some of the most important names in the entire history of the art, such as Carlton E. Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, Timothy O'Sullivan, and William Henry Jackson. By necessity, due to the fragile and difficult early techniques available to them, their approach was slow, careful, and contemplative. Years later, into the 20th century, despite the improvements in photography that provided greater choices of technology and process, a modern generation of western photographers still preferred a slower contemplative approach, in respect for the natural beauty of California and man's changing relationship to it. Three of these great photographers, each utilizing a different technological avenue as a means towards their artistic contemplation, were Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and Ansel Adams.

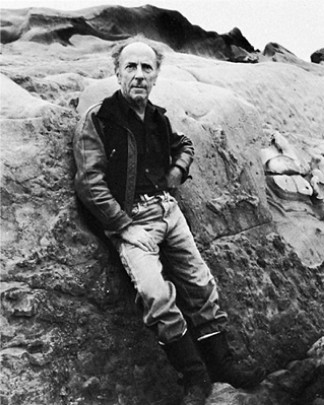

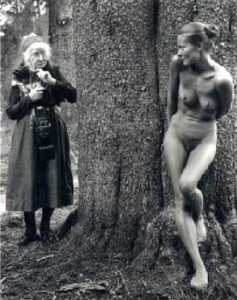

Edward Weston was born in 1886 in Illinois, but he was drawn to California at the age of 20 in 1906 to pursue his vision of photography for most of the rest of his life. Like all western photographers, he was inspired and artistically challenged by the breadth and depth of California's expansive environment. However, his own contemplative nature was extremely personal, in a sense introverted, and his approach to his craft simple, direct, and uncomplicated. For this reason I think of Weston as a "purist", somebody who looked upon his art as a pure endeavor, not needing any special tools or technology to heighten its effect.

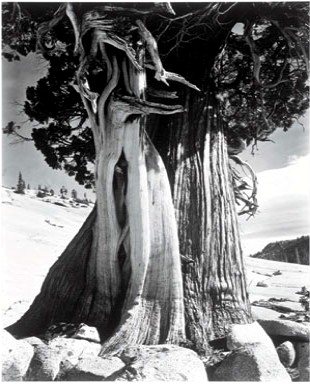

In this way, Weston's craft is the most similar to that of the classic 19th century photographers, but his subject material changed to reflect his interpersonal connection with the individual's contemplation over nature and philosophical revelation. Instead of the forest, Weston saw the trees. Instead of the mountains, Weston saw the rocks and sand. Instead of the general human experience, Weston saw the craggy and textured and sometimes unflattering features of life in a person's truthfully delineated face. By the time of his death in 1958, he was universally accepted as one of the greatest visionaries in the history of photography. His life and his theories on art and photography are well documented in countless books and biographies. And he accomplished all of this with an absolute minimum of photographic technology.

As a purist, Edward Weston used the simplest and oldest technology available to photographers in the first half of the 20th century. His preferred tool was a basic 8 x 10 inch format view camera, heavy yet adaptable, that he carried mounted on an equally heavy wooden tripod. All of his work was captured on black and white sheet film, individually loaded in holders that had to be slipped in and out of the back of the camera one at a time, which he then processed in a homemade darkroom in open trays of chemicals. The darkroom was so primitive, it did not have hot water! On colder days, to bring the chemicals up to the proper working temperature, Weston laid the trays in fitted cut-outs on his working surface, under which he had mounted a series of light bulbs. Only after the heat from the bulbs had sufficiently warmed the chemicals could he turn off the lights and proceed with his work. For printing, Weston did not use an enlarger. Since the negatives from his pictures were already a large 8 x 10 inches in size, he merely "contact printed" them against pieces of photographic paper. This entailed laying a negative inside a simple wood and glass frame, a piece of photographic printing paper was pressed against the negative with a spring-tensioned wood backing, and this frame was turned upwards on the work counter. This was prepared in the dark. When it was ready, Weston simply switched on the room's light for a brief second, and that was enough to expose the paper through the negative. Then the paper was basically developed in the same trays as the film. Much of these surprisingly primitive techniques required extensive practice and intuition, but over time were second nature to a purist like Weston.

Imogen Cunningham was born in 1883 in Oregon, and incredibly gave up on photography after her initial attempts as a teenager while going to art school in Pennsylvania. Her interest returned after an influential series of events in 1906, while continuing to pursue her art education in Washington state, that eventually led to her working under the great western photographer Edward S. Curtis in 1907. Enlightened about the practical as well as the aesthetic side of photography she learned from Curtis, she embraced the craft on a fulltime basis and established her career as a noteworthy portrait photographer within a few years. When she moved to San Francisco in 1920, seeing for the first time the energy of the humanity in that city as well as absorbing the greater natural California experience around it, her vision quickly evolved. She became more aware of the textures and hues of life that could be found in the smallest and most mundane natural forms and flora and fauna.

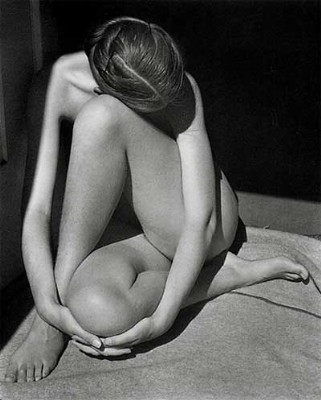

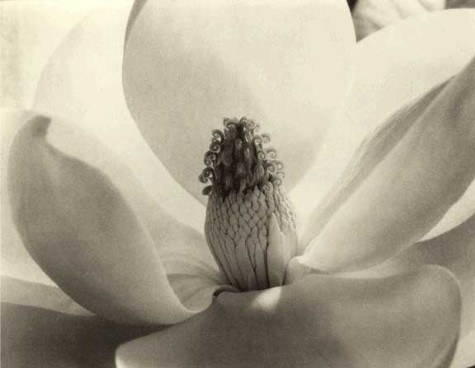

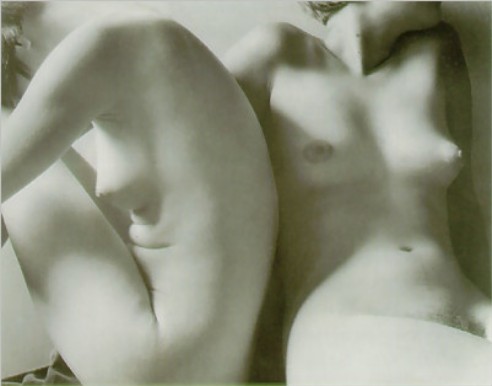

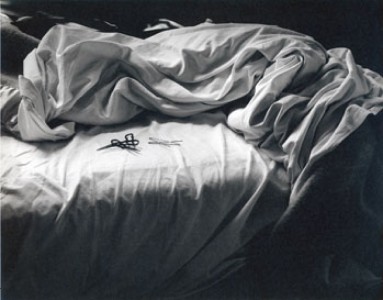

Cunningham was a free spirit, a gregarious and inquisitive and beguiling personality, who was the extroverted opposite of Weston's introversion. Her approach to photography was a form of open participation and cooperation, in which she moved more closely into her subjects with blatant enthusiasm. For this reason I think of Cunningham as a "sensualist", somebody who looked upon her art as an exploration of the sensual nature of human experience and contemplation. Her images are dominated by stunning revelations on the shapes and shadows of "things" around us, and surprising examinations of the human form. By the time of her death in 1976 (she was still working at the age of 93!), she had long established herself as the grand dame of 20th century American photography, and one of its most beloved characters.

Since Cunningham wanted to bridge the gap between herself and her subjects, she chose equipment that was smaller, more mobile, and capable of working in close quarters when necessary. Like all professionals of her generation, she used traditional large view cameras on occasion, but the preferred tool for the latter half of her extensive career was the twin-lens-reflex camera, and most specifically the high quality Rolleiflex. This camera made 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch exposures on #120 roll film. It was small enough to be very maneuverable, it used a roll of film that provided many exposures so she didn't have to stop and reload too often, and the negative size was just big enough to allow high quality enlargements. Although she did experiment with color, virtually all her most important work was taken with black and white. Although seen as an awkward tool by today's standards, heavy and somewhat ungainly to use, the twin-lens-reflex camera was actually quite liberating in Cunningham's time, and provided the degree of interpersonal "contact" she needed for her deeply sensual contemplative exploration of the subject material. The film was then developed in her home darkroom, loaded into lightproof tanks, where she used a number of different chemical processes to diligently control the shades and contrasts of the negatives. As a sensualist, the subtle possibilities in the texture and "feel" of her pictures was important, and she took great care to define them to greatest effect. These were then enlarged in the traditional manner we still use today for film, onto whatever size photographic paper she felt was appropriate for the image's subject.

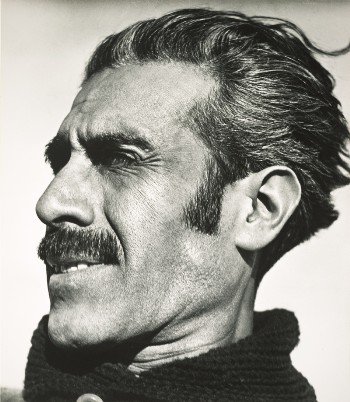

Ansel Adams was born in San Francisco in 1902, and lived the majority of his life in California. His fascination with photography and his life-long relationship with the natural environment began in his early childhood, when armed with a simple Brownie box camera during a family vacation in Yosemite Valley he recorded his first images. Although formally educated, and classically trained in piano, Adams decided early on that he was better suited and more intuitively inclined to pursue photography as a career rather than any traditional business or the uncertain world of music. Already well immersed in the arts and related philosophy, and a child of the California experience, Adams brought a classical vision to his work that was tempered by his own continuing explorations of the American west.

He did not enjoy great financial success until late in his life, but he never abandoned his quest for preserving the integrity of the American west, and most especially the fragile face of the Californian landscape. More than any other 20th century artist, the work of Ansel Adams seems to be a direct reflection of the great 19th century western photographers, but endowed with the added power of the quickly evolving technology of modern photographic techniques. Despite the advantages offered by modern techniques, however, Adams embraced the slower contemplative approach of his predecessors, and the results are nothing short of spectacular. His images are grand, thought provoking, and at times almost intimidating in their scope and philosophical impact. For this reason I think of Adams as a "mystic", somebody who looked upon his art as an exploration of the human experience before nature and an open invitation to contemplate our relationship with the cosmos. His images transcend our limited vision, and challenge us to look beyond the obvious surface of the subject material. While other photographers captured what they saw, Adams captured what we remember. By the time of his death in 1984, Adams had well established himself as possibly the greatest photographer in history.

As a mystic, you might think Adams would take a purist's view of technology, such as Weston's. However, it was quite the opposite. Ansel Adams was so obsessed with the pursuit of the perfect image that he not only embraced the most cutting edge technology of his time, but also created some of it! Adams aggressively experimented with whatever new processes and equipment that came on the market. He tried all sorts of chemicals, he worked extensively with early Polaroid cameras, he dabbled with the extremely complex Hasselblad system, he did ground breaking work in color, and much, much more. But inevitably, befitting his contemplative nature, his most important work was captured with any number of the high quality large format view cameras he used over the years, and with black and white sheet film. His preferred format, like Weston's, was 8 x 10 inches, but the comparison ends there. Adams used many different camera makers, some of the finest lesnes that have ever been designed, and every imaginable type of black and white film processed in a vast catalog of chemicals. He had his favorites, all photographers do, but Adams tinkered and experimented. His home darkroom was extraordinary. But in the end, his greatest contribution to the technology of photography was simply a new way of seeing. Adams, in an effort to codify a best possible way to capture any image, created the "zone system". This was a very precise method for measuring the amount of light in every area of a potential picture, from the darkest shadows to the brightest highlights, so that the photographer could not only make the ideal exposure in the camera, but to already know the ideal way to develop and print that picture for maximum effect. No other photographer had ever developed such a system, or thought it was possible. Adams, however, explained that the zone system grew simply out of his concept of "visualization" where he considered the eventual product of the entire photographic process and not just the subject at hand. In this way, Adams created the ultimate tool for artistic contemplation in photography, and a true exercise in transcendental vision. Copyright © 2007 David F. Silver. |